By Yannis Mavris*

(summary)

The new coalition government of premier Loukas Papademos obtained 255 votes out of a total of 300. This majority is probably not as strong as it looks. It is a well established fact that the power of a government does not primarily depend on its numerical majority. Greece’s only previous coalition government (under PM Tzanetakis) lasted only 102 days, while the “all party” government under PM Zolotas only 139 days. This axiom still applies today.

The unprecedented parliamentary majority of the current government is a product of convergence at the top, but its legitimacy among the public is not self-evident. The problem persists.

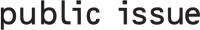

The fact that 7 out of 10 of those polled agree with the two major parties’ decision to cooperate does not necessarily reflect something deeper. It may simply be an indication of public relief at the end of Papandreou disastrous two year rule or at the fact that wholly discredited parliament speaker Petsalnikos was not appointed PM.

The change of government in 11/11/2011 has not led to a change of social perceptions as is usually the case after an election victory, or at least victory in in-party leadership contests. Public acceptance of the new Papademos government remains limited and poll numbers at the starting point do not warrant celebrations.

Three variables are used to gauge the public reception of a new government:

a)Personal momentum (popularity)

b)Trust in the new PM leadership capabilities

c)Trust in the government leadership as a whole

When it comes to the Papademos-led government, answers to these three questions reveal an impressive climb-down.

In the same poll, positive judgements progressively decline from 55% (PM popularity) to 45% (Papademos΄ leadership capabilities concerning the economy) shrinking finally to 35% when it comes to trust in the capabilities of the government as a whole.

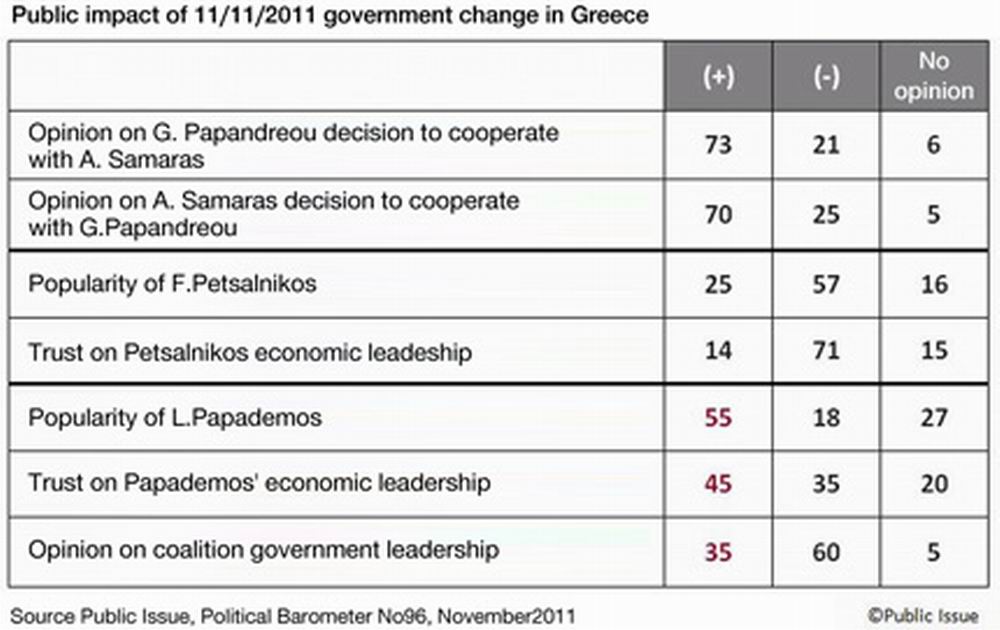

Elections, or in-party leadership contests have acted as a legitimising factor for all past prime ministers. Costas Simitis΄s aproval rate went up 35%, reaching 85% once he was elected prime minister through elections at the PASOK parliamentary group. Costas Caramanlis gained 20%, reaching 79% approval rate after his national election victory, while George Papandreou gained 26 percentage points to reach 82%. This brief “rally-around-the- flag-effect” has not been observed at the case of Loukas Papademos. After his appointment as prime minister, he only gained 7 percentage points, compared to the last poll (48% according to the Public Issue poll in April 2010). Most crucially, his approval rates are 30%-35% lower than those of his predecessors.

Similar conclusions stem from measuring voting intentions and popular support of the three governing coalition partners (PASOK, ND, LAOS). Those three parties received a total of 83% of the vote at the last elections (4/10/2009). Today, their total is estimated at 56,5%, based on the November Public Issue poll. In the past two years, their influence has weaned by a third (32%).

In the final analysis, the 35% acceptance level of the new government at its inception coincides exactly with the present real social reach of the parties supporting it. Indeed, influence of these three political parties, if we also factor in so called “undetermined vote”, i.e abstention, lies under 35%.

The attempt to transfer the source of legitimacy from the electorate to the parliament is an institutional turning point, questioning directly the historical, post-1974 constitutional compromise. A large parliamentary majority, while at the same time avoiding elections or referendum, is an attempt to counterbalance the lack of legitimacy, brought about by the loss of standing of the traditional parties. But this does not seem to be working. Politically and economically dominant social groups, “the top” might coalesce around the new prime minister, but it is not at all evident whether and how “those at the bottom” will offer their consent, especially in the absence of typical electoral channels. The wholehearted consent of the Media cannot provide legitimacy the way elections do, neither accomplish a “ideologically equivalent” result to a popular mandate obtained after an election victory.

*Political scientist, PhD, President & CEO of Public Issue

Publication of the analysis by the “www.thepressproject.gr” portal (17/11/2011)